Finding the Winter's Peace

(click on the image for a larger version)

Unlike some of our fellow mammals, we don’t hibernate. We do, though, when the winter season brings a chill peace to the outer world, move inside, into our dwellings and into the cores of our own spirits, hoping to find peace in the stillness, the dark, peace to carry us through the difficult days until Earth’s dance brings us around to spring again, and a new season of endeavor. Silent night. Holy. Or not. We huddle inside our shelters with our own kind, and hope for peace with them. The hymns ring out – “peace on earth, good will toward men”. But, far away, we know a war rages, and destroys lives not unlike our own every day. And sometimes the lives of our sons or daughters, our wives or husbands, brothers or sisters, mothers or fathers. Taken. We may wish for peace there, too.

It’s a curious word, “peace.” Lexicographers tell us it reaches back, like most of the words in our language, to a deep old root in the hypothetical common language we refer to as Indo-European, a root whose stem seems to surface in several directions, all of them bound, as it were, to the fundamental idea of binding, of fastening. So the Latin “pax,” a binding together by treaty or agreement, whence all the uses Christianity has made of the language of peace, in the context of the binding together of a community of believers. “Pax vobiscum. Et cum tu spiritu”, they said. Peace be with you. And with your spirit. But it’s also pagan – quite literally; the pagan originally was a peasant, bound to a delimited place, a piece of land, from the Latin “pagus”, a boundary staked out on the ground, from the same root. Likewise from that ancient source the Latin “palus”, the stake fixed in the ground to mark that boundary, whence we derive our “palisade”, defined by a wall of such stakes, “impale”, an unhappy use of such a stake, and even “travail” and “travel”, which passes such stakes, such milestones, as may mark the course of the journey.

On December 15th, some of Asheville’s finest poets will gather at the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center to explore the meanings they find in this rich word “peace” and speak from their own understandings of what this season holds. Thomas Rain Crowe, John Crutchfield, Laura Hope-Gill, Gary Lilley, Rose McLarney, Sebastian Matthews, and I will be rocking the Center’s rafters and, with any luck, warming spirits till they’re proof against winter.

Years ago when I shuffled off to Buffalo it was also in a time of war, another war. Notwithstanding the war and winters colder than any I’d ever dreamed, I found Buffalo humanly the warmest city I’d ever known. Perhaps it was my youth, or the common circumstance of so many of us in and around the university there, far away from wherever we’d come from, no matter how close geographically it might have been; in that clime we quickly found ourselves several states of mind removed from anywhere before. Or perhaps it was just that the natives of that place knew how to hunker down with each other, to find a peace together no matter the blizzards raged outside, and we managed to learn enough of the land’s customs to emulate their strategy. No telling. But memories of those days have lit the way into winter for me ever since, and still offer a map through the desolate season, the dark time.

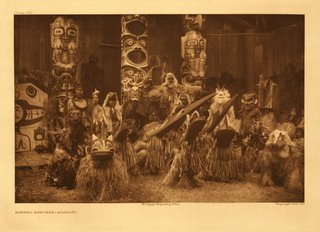

When it came time for me to do the “field work” my graduate program required, one of the things that drew me to the coast of British Columbia was that the Kwakwaka'wakw people who live there (you might know them by the name commonly used for them till the 1980s, Kwakiutl), and whose symbolic culture I’d proposed to study, had had, by all accounts, an exuberant way of getting into winter as well. For them, it was the sacred season. They worked all spring and summer to accumulate stores of food for the winter, gathering berries by the basketful, drying (and later canning) salmon by the ton, and then, as the days grew shorter, they readied themselves for winter. The assumed their sacred names; Eddie Wallace, say, became “Him Who Stands High as a Mountain.” And then it was time to celebrate, pull out the regalia, and gather to celebrate the first dance of the winter, “When the Masks Are First Brought into the House.” Until the herring and steelhead salmon began running again the next spring, they’d spend the weeks in feasting, hosting reciprocal parties (the English, using a Chinook word, referred to them as potlatches), asserting by performances their claims to dances and their winter names, contending in generosity, one clan inundating another with gifts, and being inundated in return. No one could have starved to death; it was a system of distribution, as an economist might say, that insured that sustenance and the necessities of life reached even the most humble members of the group, however bad the external weather. These celebrations, of course, these gatherings around the long houses’ central fires, rang with song and dance, with myth and story.

The British made such festivities illegal, of course, given that they weren’t exactly Christian (the missionaries shaped the British Empire’s foreign policy even as they sometimes shape ours), but the people persisted in secrecy; celebrations morphed, changed clothes, and continued. And by the mid nineteen seventies … well, the ban on the potlatch had been lifted, and the fine citizens of Alert Bay, British Columbia, certainly knew how to throw fine parties, whether the music of choice was traditional song or rock and roll.

Here in the mountains, now barren of leaves, the Solstice bears down upon us, so let’s gather together, break out the masks, and make some joyful peace together as we head into winter. With the help of our poets and musicians, we’ll get our spirits warm enough to live in concord no matter what snow, rain, wind and chills try to trouble us between now and spring.

Where: Black Mountain College Museum + Art Center

56 Broadway, Asheville

When: December 15th, 8:00 PM

Admission: $7/$5 members and students with ID.

For more information, go to the Center's website.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This post appeared in different form in the December issue of Rapid River.

The photo is by Edward Curtis, and features masked dancers from a Kwakwaka' wakh community c.1912.

Labels: BMCMAC, British Columbia, Kwakwaka'wakw, poets, readings

1 Comments:

If you enjoy Edward S. Curtis's work, you will surely want to see The Indian Picture Opera. This is a remake of a Curtis 1911 slide show and lecture on DVD. I found it on Amazon. Its about an hour long, and an amazing documentary.

Post a Comment

<< Home