Exploring The Dao With Thomas Meyer

Eugene O’Neill might never have written Long Day’s Journey Into Night, or any of his other dramas, except that tuberculosis forced him to bed, to a long reflective physical inactivity, and required of him a different life. Poet William Carlos Williams, felled by a stoke in 1951, had to learn to write all over again, but went on to produce The Desert Music, Journey To Love, and Pictures From Brueghel, three of his most moving testaments to the powers of relationship and of the imagination, in his final decade. For both of these men, experience of severe physical disability brought discovery or rediscovery of the vocation of writing; it drew them into deep creative work.

Eugene O’Neill might never have written Long Day’s Journey Into Night, or any of his other dramas, except that tuberculosis forced him to bed, to a long reflective physical inactivity, and required of him a different life. Poet William Carlos Williams, felled by a stoke in 1951, had to learn to write all over again, but went on to produce The Desert Music, Journey To Love, and Pictures From Brueghel, three of his most moving testaments to the powers of relationship and of the imagination, in his final decade. For both of these men, experience of severe physical disability brought discovery or rediscovery of the vocation of writing; it drew them into deep creative work.But, of course, Thomas Meyer didn’t think of these predecessors when he found himself flat on his back, unable to sit or stand, in 1989. He simply wondered what on earth he would now do.

Thomas had begun writing when still a teenager in Seattle, Washington, and submitted his first poem to a magazine when he was all of sixteen. He was already at that age a veteran of the arts, having been a child actor, beginning at age nine, in TV ads and summer stock theater. His determination to write persisted, even though, at that historical moment in Seattle

the shadow of Theodore Roethke loomed large. Classmates of mine had older siblings who'd been in his writing workshop where — we had heard stories — much emphasis was put on the name to write under, what magazine to send which poem to, and how to make your regional images appeal to a national audience. All of this, even then, struck me as another screwiness of America post World War Two. Writing, it seemed, wasn't about writing, it was about getting into print. Were we talking about poems or corn flakes? (from Tom’s article “On Being Neglected”)It wasn’t uncommon, Tom amplifies, for Roethke, as he went through the roll of his students, to remark “Don’t worry, I’ll come up with a name for you.”

That local focus factored into his choice, when the time came, to go east for college. He wound up at Bard College, which had one of the premier programs in American literature in the 1960s and 70s, and was just up the Hudson from New York City. Bard faculty member Robert Kelly, himself a widely published poet and editor, helped him find his footing in the New York literary world, and by 1968, at age twenty-one, Tom was publishing poems in Clayton Eshleman’s great magazine Caterpillar; that’s where I first read him.

In the couple of decades following, Tom found audience and extensive publication for his poetry. His work with partner Jonathan Williams on Jargon Books brought him interaction with some of the most visionary writers and artists of the era, and extended his contacts. Gradually, though, publication came to mean less to him; it had never been a primary focus, and slowly became even less important. As he writes:

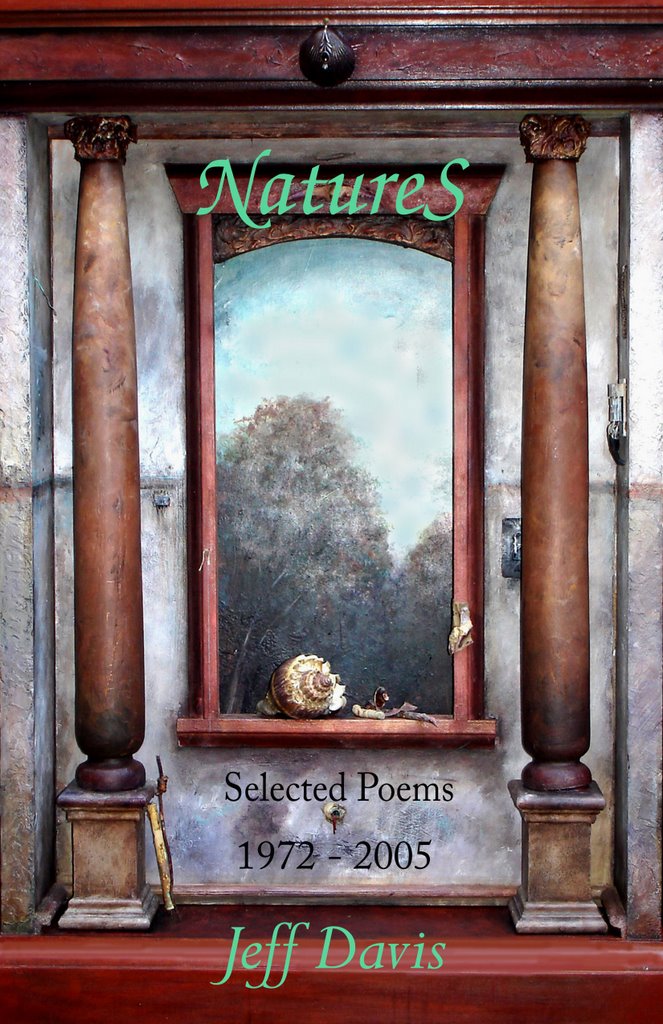

There were so many poets who wanted to get into print that by my late forties I felt I should step aside; in effect become neglected. I'd had more than a fair share of not wide but close attention; and at least three 'ideal readers.' So too, I'd been lucky, always having the time to write when I needed or wanted it. Perhaps that's why I think about being neglected the way I do. But who's to say that my luck isn't the result of always writing when I needed or wanted to? (again from “On Being Neglected”)(Luckily for us, many of the poems from those lucky decades are collected in At Dusk Iridescent, published by the Jargon Society in 1999. There are some selections from it up at the Nantahala Review site.)

In the enforced immobility of the first days after his back injury (Tom writes from his home near Highlands: “It was one of those mysterious things. I had an exercise routine and somehow bent this way and not that, and wrenched the lower back, which was sort of painful the same day. But the next morning, at the bathroom sink, shaving, I bent to look in the mirror and WHAM! I was on the floor. Muscle spasm. And had to crawl back to bed, couldn’t stand upright for about five days.”), in those days of pondering, Tom found a project that spoke of the wisdom of inner stillness and provided new ways to assess his position in life, that provided new perspectives on the question of what, in fact, constitutes “success”? While he’d worked a bit with the I Ching, the great Chinese divinatory classic, one of the world’s oldest books, as a young man, he’d never found it particularly hospitable. Now, though, he did find it welcoming. “After a month or two, I had the amazing feeling of being embraced by something, of being held”. He’d been accepted, perhaps, into the fold of the ancient lineage of human imagination that the I Ching, that “crazy compendium of poetry, songs, legends, recipes, and sayings,” as Tom describes it, embodies. He’d not been interested initially in the I Ching’s divinatory aspect (its principle use, for millennia, has been divination), but he came to appreciate that, too, as “one of its many dimensions. Divinatory practice,” he says, “is a way to calm you down, to get you to stop thinking so things can work out.”

He also explored the other great classic of Taoism, the Tao Te Ching – or, as Tom, following contemporary conventions for transliteration, terms it, the Daode Jing. And he found it a text that spoke to him as well. “The Dao,” Tom says, “is of as profound an order as the I Ching, but it offers silence and the idea of a positive emptiness as a space in which something can happen.” For the next decade, as he slowly healed, unable for most of that time to sit for any extended period – he had to work standing at a high desk (“like a scribe”, he says) – he developed his understanding of these texts. He read the Dao every spring, all of it, character by character, one chapter a day, in Chinese. He gradually worked at translations, first of the I Ching, building a concordance of its many characters, some of them rare in contemporary Chinese, one found only in its ideograms, and then of the Dao. As he notes in the afterward to his version (now to see the broader light of day),“Though I tried [to translate it], I didn’t press too hard, heeding the [book’s] advice to look for and follow that inherent, natural course of things themselves.” The texts and his dictionaries became his constant companions, something he carried with him everywhere, like, he says, “a bag of needlework.”

As Tom’s translation emerged, he gradually found the voice of the text. As he notes in the Afterward,

The tone was conversational, not canonical. Honesty and simplicity foremost, rather than piety or complication. There were no themes, ideas per se. Following one upon another, things circled, darted away, appeared again, or vanished altogether, with the natural ease and bonhomie of good talk.

“Of course,” he adds. And that voice seemed to him consonant with the traditional story of the origins of the Dao, which, unlike the I Ching, is reputed to have had a single author, laozi – or, in the older, traditional transliteration, Lao-Tzu – though the name itself simply refers to an “old man”. Here’s Tom’s account of the story:

Many years ago an old man lived in the capital of a place called China. He was the emperor’s librarian and renown for having read everything there was to read. When the philosopher Confucius paid him his respects, he came away saying:

Birds fly. Fish swim. Animals run.Tom’s now ready to emerge from his remote hermitage and share one of the results of his long undertaking, his translation of the great Daode Jing. On March twenty-second, at 7:00 PM, Tom will read from his newly published version at the Black Mountain College Museum + Art Center (another of the Center’s extraordinary programs), and introduce it to the world.

They can be caught, shot, or trapped.

But this old man is like an air-borne dragon.

He can’t be snared.

Then as now, things could not get worse, but did. Big troubles were afoot. Those with power abused it. Those without grew cunning and two-faced. The old man finally could stomach no more greed, dishonesty, or corruption. The time had come, he told himself, to get out of China.

He climbed upon an ox, and leaving behind what little he owned, headed west, toward the high mountains of another country. When he reached a gate that led up a steep pass, the border guard stopped him, and said:

I recognize you and cannot let you go until you tell me everything you know. Otherwise we will see all that is worthwhile swallowed up by all that is not.

The old man welcomed a rest. The sun almost down, a bottle of wine opened, the two sat in the little station hut. The guard listened as the old man told him what he knew, which he said was not much. In fact, the moon was still in the middle of the sky when he got up to leave.

He was never heard of, or seen again. The five thousand words spoken that night are all that is left of him. And that, in the mind of their speaker, was five thousand too many.

For more information, visit the Center’s website or call 828-350-8484.

For more on Tom’s translation of the Dao, read on; the next post is a “test of translation” that looks at Tom’s version and compares it to previous translations – and provides some background on the text of the Dao as well.

********************************

This post originally appeared, in somewhat different form, in Rapid River Art Magazine Vol. 9 No. 7, March, 2006. Original content © 2006.

The photo of Thomas Meyer is by Reuben Cox.

Labels: Further Studies, poets, Reuben Cox, Tom Meyer

2 Comments:

Great to see you focusing on Tom and his work!

Yes, thank you for this posting. It reveals a lot to me and leads me to contemplate not only Tom M's work but my own.

Andrew

Post a Comment

<< Home