Perhaps still to appear ... a celebration of Jonathan Williams

Like many another such institution, the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center usually sends a newsletter to members and other interested parties once a year or thereabouts, just to let all know what it's been up to, what exhibits it's hosted, what significant presentations, readings, and performances it's brought to the community, and offer an occasional bit of Center news. Well, this year the winter came and went, and the Center's sole staff person, the almost-tireless Alice Sebrell, continued to find her time consumed by the many many day-to-day tasks involved in managing the exhibits and events on the Center's calendar (all part of an intensely-programmed year-long series featuring the women of Black Mountain College), and the newsletter languished. Perhaps it will someday appear. In the meantime, having just done another Wordplay show featuring Jonathan Williams, I thought it might be good moment to dig out the newsletter article about the celebration of his life and work that the Center held last summer. Parts of it were developed from earlier posts here, and so might sound a bit familiar if you've already gone through the Natures archive in search of words about Mr. Williams; I've revised it to correct temporal references that were current when it was written last fall.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Jonathan Williams: Last Flight for the Loco Logodaedalist

What's the old maxim? Don't speak ill of the dead? There's a curious metamorphosis that takes place after death, besides the body's moldering. If we believe less these days in a reckoning before a juridical God (or Pluto, or Osiris), we know there's still a reckoning of a different sort, one that affects not our afterlife in the world beyond, but our afterlife within the community and culture of which we're each a part. For those who lead public lives, especially our artists and writers, the departure sometimes offers a moment of public reconnection, new recognition that what the artist has done has significance and resonance, beyond whatever claims the contending artist might have made for it. Or not. And sometimes ... well, Melville's death was little noted in 1891, eliciting but one obituary; re-appraisal, and the recognition of achievement it provided, had to wait for thirty years and the publication of Raymond Weaver's 1921 biography; his edition of Melville's last work, the short novel Billy Budd, in 1924; and texts like D. H. Lawrence's 1923 Studies in Classical American Literature.

The death last year of Jonathan Williams, late of Scaley Mountain, near Highlands, NC, seems happily to have spurred the world to give his work a more immediate second look. Ron Silliman, one of the leading conceptual poets of the generation that came of age in the 1970s, shortly after Donald Allen's 1962 anthology New American Poetry had reshaped the landscape of American verse, in his obituary for Jonathan included a fine appreciation of Jonathan's Blackbird Dust, and noted that he'd reviewed Jubilant Thicket, Jonathan's last collection, as "one of those absolute must-have books of poetry." And the Electronic Poetry Center, one of the primary Internet source sites for poets who appeared (as Jonathan did) in the Allen anthology, as well as their spiritual progeny, has now created a page for him with an array of links to the part of his work that's made it to the web, and to a slew of articles and appreciations that help provide context for the encounter with his work. Such notice, however belated, is always welcome.

A curious fact about Mr. Williams, of course, is that he didn't start out to be a poet at all. When he came to Black Mountain College in 1951, it was to study with photographer Harry Callahan, who was teaching in the summer session. Charles Olson, who headed the college and taught courses in writing, cosmology, and "the present", recognized Williams' great gift as a writer, though, and - shazam! - writing soon became for Williams the primary creative focus. He'd founded Jargon Press by the end of 1951, when he was just twenty-two; he'd go on to publish under the Jargon imprint close to a hundred titles by the brilliant wildcat pioneers and demotic outliers of American arts and letters over the five decades after the college as a formal institution ceased to exist.

Fortunately, he continued to use his camera, too; thanks to him, we have images of many of the denizens of Black Mountain College during their time together there - Charles Olson, for instance, sitting at his desk in his quarters at the college writing an early Maximus poem. And Robert Creeley, who used one of Jonathan's photos of him on the cover of 1969's The Charm, which collected poems from the Black Mountain era. Poet Thomas Meyer, Jonathan's longtime partner and co-conspirator in things Jargon, said recently that Jonathan had shot thousands of photos over the years, many with a Rolleiflex twin-lens reflex camera that used a medium format film - and so provided negatives with much higher resolution than those from 35mm cameras. He later favored the Polaroid SX-70, whose print format was of a similar size. When Jonathan and Thomas would join friends for dinner, Jonathan would often use the Polaroid to shoot everyone present and document the antics of the occasion. In the fall, he'd go through the stacks of shots from the previous year, and mount them in albums. He'd also assemble slide shows of whatever images had caught his eye - poets, landscapes, architecture, landscapes, art works. Williams, according to Meyer, continued taking photos through 2004. By 2006, when the transparencies were archived at Yale's Beinecke Library, he'd amassed "several thousand", including a "core collection" of about 2400. Two of his published titles, 1979's Portrait Photographs and A Palpable Elysium, published in 2000, drew on this vast photographic work.

Last summer Asheville's Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center helped us give Jonathan's work as a photographer the same sort of second look that his poetry has begun to receive. From June 13th thru September 20th the Center hosted a show of Williams photos, many of them fine black and white prints that beautifully register and find form in occasions during his years at Black Mountain. Others, some of them in the vibrant saturated colors with which he later loved to work, feature Black Mountain artists and writers, like M. C. Richards and Robert Duncan, who came into the orbit of his eye after their years at the college. Williams became, I think, a master of the post-modern portrait, situating his subjects in vivid color fields or apparent contexts that give the images depth and dimension.

Jonathan made it clear that he wanted no memorial services - but while the show was up, the Center also celebrated Williams' work as a writer, hosting a reading on July 19th by friends from far and near, some of whom had known Williams for decades, some who'd known him just a few years. Writer Tom Patterson, one of the former, organized the event, and set the order of reading for the night. The readers had been corresponding for several weeks before to declare their preferences for poems or prose selections that defined Jonathan in his particularity for them. I found that I was reminded of the old Buddhist teaching story about the blind men and the elephant; for some of us Jonathan was a winnowing basket, for others a plowshare, for others a column, for others a rope. It was fascinating to hear these various takes on Jonathan converge; I'm hoping we got close to providing a glimpse of the whole elephant before we were done.

Readers included Aperture editor-at-large Diana Stoll; art historian James Thompson; poet/teacher Jay Bonner of The Asheville School, and his daughter Hannah; photographer Reuben Cox; longtime Jargon Society Treasurer Thorns Craven; poet Jeffery Beam; Meyer; Patterson; and myself.

Jonathan was probably best known for his humorous work, and he did humor well - perhaps a rare talent in any age, but one that seems particularly scarce these days. In the course of his long career (I almost wrote "careen"; he moved right along), though, he explored many territories of poetry, from the visual (see the original edition of Blues & Roots/Rue & Bluets), through the procedural (portions of 1964's Mahler were composed by using a "Hallucinatory Deck", "a personal alchemical deck of 55 white cards on which are written 110 words, - the private and most meaningful words of my poetic vocabulary"), to the poem of found or discovered language. One of my favorites, though, (and one of the poems I read) is one of his more conventional poems ("conventional" at least in the context of The New American Poetry), one that's grounded deeply in the world of nature, and celebrates that grounding:

The Deracination

definition: root

"a growing point,

an organ of absorption, an aerating organ,

a good reservoir, or

means of support"

veronica glauca, order Compositae,

"these tall perennials with

corymbose cymes of bright-purple heads of

tubular flowers

with conspicuous stigmas"

I do not know the Ironweed's root,

but I know it rules September

and where the flowers tower

in the wind there is a burr of

sound empyrean ... the mind

glows and the wind drifts...

epiphanies pull up

from roots

epiphytic, making it up

out of the air.

The evening was a fine celebration, I think, of the remarkable Loco Logodaedalist, the Sage of Scaly Mountain, Mr. Williams, and his work.

Jonathan, hale and farewell.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

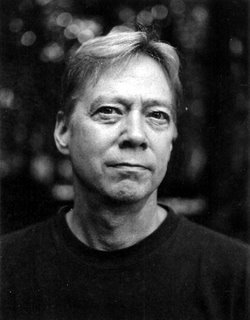

Photo: Jonathan Williams by Reuben Cox.

Labels: BMCMAC, Jonathan Williams, Reuben Cox