Ancient Music Indeed

Kevin Drum is a Political Animal, but every now and then posts in areas that are peripheral to the political brouhaha of the day. Yesterday he posted a short article citing a study of the pitch of women's voices in different cultures; turns out that that pitch is more a matter of culture than biology. Here's what he quoted, from Tyler Cowen's original post about the book:

Women in almost every culture speak in deeper voices than Japanese women. American women's voices are lower than Japanese women's, Swedish women's are lower than American's, and Dutch women's are lower than Swedish women's. Vocal difference is one way of expressing social difference, so that in Dutch society, which doesn't differentiate much between its image of the ideal male and the ideal female, there are few differences between male and female voice. The Dutch also find medium and low pitch more attractive than high pitch.Kevin adds this:

Which goes to show how powerfully culture worms its way into things that are widely assumed to be mostly biological. Most people believe that women have higher pitched voices as a matter of simple physiology, but it ain't so. It's mostly cultural, and anyone who watches old movies can attest to how the ideal of female voice has changed over the past 70 years.

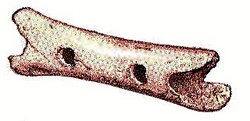

Intriguing stuff. His reference made it seem likely that the post from which he drew it might be worth a read, so I clicked through. Kevin had gotten the heart of it, but one of the commenters on the site had posted a link to another article that he considered relevant, and that article was fascinating indeed, and bears on the deep history of music that I hinted at obliquely last week in my post expressing compassion for Bill Knott, who dislikes music. While I haven't taught anthropology since the early 90s, I do continue to read books and articles on ethnology and paleontology, but I'd missed news of what's become known as the "Neanderthal flute". It's a portion of cave bear femur pierced by two in-line holes, with apparent portions of two other holes at either end of the gnawed bone, also in line with the others. It appears the holes are not evenly spaced, but spaced in the way they would have to be to produce the tones of a diatonic scale. And there's little doubt that it's between 45,000 and 80,000 years old, which would make it by far the oldest musical instrument yet found. It's age would also mean that it was made not by modern homo sapiens, but by the Neanderthal residents of the complex where it was unearthed. That's heresy for many paleontologists, and there've been rivers of ink and bits spilt to debunk the claim, to assert that the holes were made by gnawing wolves, etc., notwithstanding that the odds that accidental, "natural" causes could create such spaced, in-line holes appear to be one in several million. Wikipedia has a good review of the controversy here.

I don't have any special expertise in the area, but wouldn't be surprised if the flute were eventually proved to be genuine, perhaps by the discovery of another of similar antiquity. Notwithstanding the hulking Neanderthal stereotype (a bit of species-based prejudice at work), our Paleolithic kin actually had a fairly sophisticated, if not elegant, tool kit; their Mousterian points, hand axes, and blades are functionally made, and it's certainly within the range of possibility that they could have drilled the femur to make music. But even if it's not a flute, but a fluke of nature, we already know that music pre-dates the use of writing (and all that writing entails, including history) by thousands of years, thanks to the discovery of several flutes, some made from the leg-bones of cranes, in Jiahu, in Henan Province, China, that date to some eleven thousand years before the present.

No one knows exactly why, but the capacity, even need, to make and enjoy music seems built, for some reason, into our biology. So to reject music, it seems to me, is to risk estrangement from a core part of the psyche. Whatever the uses cultures have made of it, whatever the defects of character of those who make it (and I've known some gifted pricks, and prickettes, myself - but, then, poets are not always paragons of virtue or enlightenment either), it seems to me one of the crucial activities that binds us into the rhythms and melodies of the world. As much as I enjoy and admire Bill Knott's work, I'm tempted to deluge him with CDs and tapes until we can find some music that he enjoys. Balian Gamelan, perhaps? Work of Rafe Vaughan Williams, or perhaps the contemporary American composer Eric Ewazen? Messiaen? Or maybe the guitar work of Steve Kimock? At least he probably wouldn't have heard any of it yet in the supermarket.

Of course, my doing that would probably make him more resistant yet to the releases from the cognitive, verbal levels of consciousness that music provides, so I won't. But if Bill should decide to investigate music further, I'd be glad to do what I can to help out.

Labels: Further Studies, music, Neanderthals, paleontology

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home